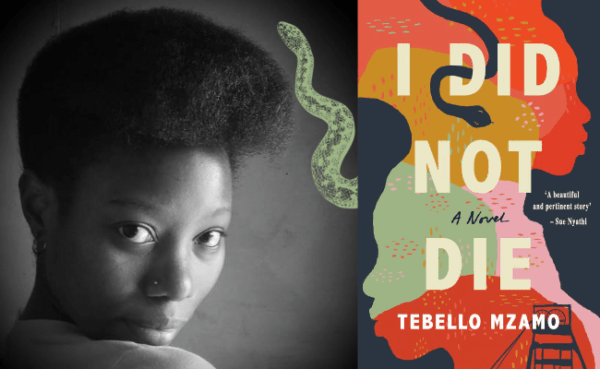

Photo of Tebello Mzamo and book cover: NB Publishers

I did not die

Tebello Mzamo

Publisher: Kwela

ISBN: 9780795710735

Tebello Mzamo’s slow-burning debut novel I did not die opens on a dramatic scene. A snake wends its way across a floor towards a dozing family. The mother, seeing danger in time, sweeps up her children and runs from the house, averting disaster. The snake (hastily dispatched by the men of the village) is a harbinger of trouble. Nthathisi, the bewildered, angry mother, is raising her children alone in Lesotho, her partner Botho Pere away for long stretches of time in South Africa, where he earns a pittance working on the mines. This compact novel unfurls over 220 pages, abjuring resolution in favour of a dallying story whose open-endedness is truer to life in the way it orbits around the lives of its characters.

This novel enacts itself with the slow dissolution of black life under the wretched conditions of economic migration. Botho’s absentee status as husband and father (in a structurally clever authorial sleight of hand, he only appears three chapters in) destabilises the fragile family structure in all the expected ways: he is all but a stranger to his children, and an estranged partner to his wife. His and Nthathisi’s storylines entangle and come apart, as their brittle bonds twist and fray.

Botho has little to show for the tracts of time he spends away. Returning from a long, unexplained absence, he sees his own house, which sticks out dismally among his neighbours’ comparatively tidy metal-roofed houses, “like a shaggy black sheep – the only thatched house in the neighbourhood” (25). The first person he encounters is his dyspeptic neighbour Mokoto, who is despised and feared throughout the village on the suspicion that he practises witchcraft. He reaches his house (the journey from disembarking the taxi to his front door is Odyssean) and finds that his wife is not at home (a recurring motif, for good reason). When Nthathisi sees him, her anger washes back and forth: he is thinner than she remembers, and his pants are ominously well-ironed. She wonders to herself, “Could this still be the man who had once said that he wanted to share a life with her?” (47).

A certain kind of mannish novel carved a path for itself in the 2000s and beyond: black men swallowed up by the insatiable economic Gomorrah. These novels tended toward a nail-bitten realism that spoke in the urgent argot of black life. They entreated with brutality and economic uncertainty; with sly, makeshift joy and hapless live-and-die fatalism. I steeled myself to encounter this tired literary trope in this novel, and indeed there is something of those novels’ rube predictability in how Botho is written. He’s a frame around which certain ideas about manhood have been wrapped, and he stumbles foolishly through a life that seems to lurch ever closer to ruin. And yet he remains on the right side of our readerly sympathies, even as he blunders. I found myself willing him to get it together, even as it became increasingly clear there was no “it” to pull together in the first place.

Mzamo deftly and movingly sketches the precarious conditions of life; we see in the emotional torsions of this novel’s characters how life plays out for those who extract wealth but don’t benefit from it. We also see what the repercussions of that life are for those who are drawn into the whirl of instability. Botho’s whirling frustration at his inability to shore up his life against the ravages of poverty are well realised. His inner discord never becomes trite, as we witness the world darken around him:

He had lost a lot of weight. His trousers were loose on his body as he crossed his legs … He felt light now, like one of those flowers you could disintegrate just by blowing air at them. Tap him with a finger on the shoulder and he would collapse. (107)

But Nthathisi is the stand-out character, a self-possessed black woman whose upward trajectory is destroyed by her relationship with a selfish man. Her growing disenchantment with the patriarchal scene into which she has been cast, and her awareness of the scarcity of her options, brings on a mental crisis, the rendering of which is sensitive and astute. When she discovers the cruel truth of Botho’s long absences, her sadness and despair are a visceral flat note:

Botho how could you. How could you do this to me. I hate you with all my heart. Do you hear me, Botho. I hate you. She had ended the letter by telling him not to even bother himself with visiting them: We don’t need you. (107)

The novel leans against our understanding of the post-Marikana era, and how that cataclysmic event exposed the way that the wounding effects of that most exploitative of our extractive economies radiated outwards. Mzamo constructs a fabulistic story whose supernatural dimensions (the witch neighbour, the sinister talking house) are a way to talk about the tragedy of hegemonic violence. This the novel achieves with a well-struck sense of pathos, which is perhaps its strongest quality.

Many South African debut novels are off-puttingly imprecise in their storytelling. Characters behave like stage actors in a bad production, sweating where no sweating is called for, improbably shouting or screaming in the middle of ordinary conversations, spouting absurd pellets of dialogue, being emotionally uninteresting, or doing other things that carelessly wick away verisimilitude. While I did not die is guilty of some of these dramaturgical missteps, it doesn’t suffer too badly for their presence. If the authorial voice is largely unburdened by anything particularly distinctive (a hallmark of workshopped novels), neither is it completely anonymous. The narrative is stronger on description than it is on dialogue: conversations are mostly mundane, plot-advancing thoroughfares. And while the sex scenes are poor, and so an infliction upon the reader, they convey something of the toxic attraction Botho and Nthathisi feel for one another.

I did not die’s major weakness is its frustrating plot drift. There is not much in the way of narrative tow: whole years are skipped over with dizzying nonchalance (“over the next two years”), a conceit that becomes clumsy when overused. The novel also bookends its chapters with a kind of tragic chorus, but the effect doesn’t quite come off. By the end of the novel, I felt as though I’d been wading through several broadly interlinked episodes that, in the end, failed to cohere convincingly. The strange, curdled malevolence of the neighbour, Mokoto, skulks in the corner without ever resolving into anything tangible. The subplots involving the various children feel weakly plotted. Botho’s despairingly quixotic final act, while foreshadowing the rending piling up of death at Marikana, feels like a largely gestural demise, and one that marks an unsatisfying petering out of the story, even as it wants to be read as a haunting.

The nagging problem is that I did not die seems to want to proffer its tragedy as a powerful critique, but the mechanics behind it are inchoately drawn, so that it ultimately feels like a morality fable in which the lesson has gone missing. I think that there’s a more interesting novel lying latent within this one. At the human level, I did not die is a spiralling social commentary, kind of a working-class Scenes from a marriage meets Joel Schumacher’s Falling down in its focus on the slow falling-apart that can happen despite all of life’s promises of prosperity. But that story isn’t accessible to us, so what remains is a flawed but readable debut, whose sadness belies its title.

Also read:

The post <i>I did not die</i> by Tebello Mzamo: a book review appeared first on LitNet.